Abstract

The introduction of compulsory bicycle helmets in Australia was driven by a belief held by doctors and pushed through by politicians without concrete evidence. While this move seemed well-intentioned, it ultimately disregarded potential side-effects and valuable research. Government findings even cautioned against soft-shell helmets due to the risk of brain injury, suggesting an upgrade in helmet standards. Instead, the standard was weakened to accommodate soft-shell helmets, making compulsory legislation more convenient.

In 1988, a comprehensive study revealed an alarming truth: increased helmet use was positively correlated with a higher fatality rate among cyclists. Shockingly, this evidence was ignored. In 1989, Australia became the first nation to enforce compulsory helmet laws. The lack of plans for assessing its effectiveness was troubling.

As predicted by the 1988 study, the risk of accidents and injuries grew. Today, Australia’s cycling serious injury rate is a staggering 22 times higher than best practice. This discourages many Australians from enjoying the health benefits of cycling. The public health costs are substantial.

The implementation of helmet laws led to a surge in accidents and injuries. Australian state governments reacted by commissioning “studies” aimed at obscuring these issues or denying the decline in cycling. The fact is this legislation has not made cycling safer. It has harmful side-effects. It does more harm than good.

It is time to recognize the shortcomings of compulsory helmet laws and reconsider their impact on public health. As of 2009, Australia’s federal government has abandoned its compulsory helmets policy, signaling the need for a more balanced and evidence-based approach to cycling safety.

blank

Table of contents

Forming the belief

Promoting the belief

Preparing for legislation

Setting the law

The illusion of safety

The consequences of negligence

Denying the failure

Adding scaremongering tactics

A surprising increase in accidents and injuries

The neglected human factor

Start of renewal

Summary

blank

Forming the belief

In mirroring the success of helmets for motorcyclists, a prevailing belief emerged that cyclists required similar head protection. The Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS), a proponent of safety measures like compulsory seat belts and motorcycle helmets, aimed to make bicycle helmets the “third major step” in enhancing safety.

A leap of faith arose that a bicycle helmet law would be effective like the motorcycle helmet law

This initiative, however, was propelled more by faith than evidence. Despite the absence of scientific proof, doctors fervently advocated for a helmet law, with the RACS asserting in 1978 that cyclists should wear helmets without providing concrete efficacy data. Dr Trinca said:

“We could perhaps worry a little less about and take a little less time in proving what is precisely right according to all standards … As doctors we are impatient. We cannot wait for 2 or 3 years evaluation.”

Dr. Trinca’s candid admission encapsulated this mindset, stating essentially that the medical community believed in mandatory bicycle helmets and saw no need to wait for conclusive evidence.

This rush to a “remedy” without robust trials poses a paradox within the medical discipline. While the field demands meticulous trials for new drugs to ensure minimal negative side-effects, the RACS chose to impose a helmet solution based on belief rather than evidence.

Contrary to countries with the lowest rates of cycling injuries that focus on preventing accidents, the push for compulsory helmets in good faith may have inadvertently jumped to conclusions. The RACS had championed an unproven theory.

blank

Promoting the belief

Pushed by the RACS, politicians were under pressure to “do something”. In 1978, the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Road Safety recommended that:

“cyclists be advised of the safety benefits of protective helmets and the possibility of requiring cyclists to wear helmets be kept under review”.

But the evidence submitted to the committee as published in Hansard includes nothing on the efficacy of helmets as protection. Indeed, in the reports of later parliamentary committees that led to the present policy, the earliest study cited (by McDermott and Klug) is dated 1982.

They took efficacy for granted. They assumed helmets “protected”, without assessing side-effects.

Helmets were promoted by people with good intentions,

but limited understanding of cycling safety.

The government responded with a campaign to promote helmet wearing. In Victoria, the RACS did likewise, even putting a case for compulsory wearing to the Premier in 1982. Helmet manufacturers started advertising bicycle helmets that became their most profitable product. By the end of the 1980s about 30% of cyclists wore helmets.

blank

Preparing for legislation

The 1978 inquiry issued a final report in 1985. It recommended that cooperation of states and territories should be sought to

“review the benefits of bicycle helmet wearing … and unless there are persuasive arguments to the contrary introduce compulsory wearing of helmets by cyclists on roads and other public places”.

A federal parliament committee was set up in 1985. Early in the course of its inquiry (before it had reviewed all the evidence), it said:

“It is, of course, this Committee’s belief that all cyclists should wear a helmet to increase cycling safety.”

The committee had made its decision prematurely. Like the 1978 committee, it took efficacy for granted. Its biased mandate included a pre-determined objective to introduce a helmet law. The committee did not conduct a cost/benefit analysis. It also failed to consider potential side-effects of a helmet law.

Legislation is sometimes pushed through, not because it provides compelling benefits,

but because those pushing for it cannot see compelling evidence NOT not to introduce it.

Legislation was pushed through as a biased committee could not see compelling evidence NOT to introduce it. This reverses the onus of proof. Proponents of a law are not required to demonstrate it provides a net benefit. They simply assert that they cannot see compelling evidence against it. This lacks important sanity checks.

In 1987, the Federal Office of Road Safety (FORS), a government agency, published research on helmets. This research highlighted serious deficiencies with bicycle helmets:

“The substantial elastic deformation of the child head that can occur during impact can result in quite extensive diffuse brain damage. It is quite apparent that the liner material in children’s bicycle helmets is far too stiff …

rotational accelerations were found to be 30% higher than those found in similar tests using a full face polymer motorcycle helmet. More work needs to be done in this area as there would seem to be a deficiency in rotational acceleration attenuation that may be the result of insufficient shell stiffness ….

a high proportion of impacts were to the lover facial and side of face areas and it is imperative that the temporal area be more fully protected than it is by current bicycle helmet designs. “

Bicycle helmets are designed for adult heads. They are too stiff for children deformable heads.

Despite warnings they can cause brain damage, helmets are promoted as “protecting” children.

The research recommended changes in the Australian helmet standard to rectify these deficiencies. 25 years later, none of these deficiencies have been rectified. Australia still does not have a separate standard for child helmets. Helmets are still not tested for rotational acceleration, the main cause of brain injury.

There are two types of brain injury: focal and diffuse. Focal injury occur when the skull hits a surface. Diffuse injury occurs when the head rotates quickly. Although the skull is intact, there can severe internal brain injury. This article reports from a surgeon who operates on cyclists:

” “The ones with brain swelling, that’s diffuse axonal injury, and that’s bad news” …

the whole brain is shaken up, creating many little tears in its inner structure …

Such patients undergo personality change, can contract epilepsy and have difficulty controlling their anger. They might become unemployable. Depression is a common accompaniment to brain injury. Rosenfeld sees patients’ families shattered, too. “They’re never the same. It often leads to marriage disharmony and family breakdown.” …

Rosenfeld’s opinion is candid. “I don’t know if [helmets] do much to protect the inner part of the brain,” “

A New Zealand doctor reports:

“cycle helmets were turning what would have been focal head injuries, perhaps with an associated skull fracture, into much more debilitating global head injuries”

A soft-shell helmet is a piece of polystyrene covered by a layer of plastic less than 1mm thick.

It can protect in a minor accident. However, it is not designed to protect in a serious accident.

blank

A soft-shell helmet tends to disintegrate on impact, absorbing little energy. This crumbling is what many people mistake the helmet for as having saved their life:

“The next time you see a broken helmet, suspend belief and do the most basic check – disregard the breakages and look to see if what’s left of the styrofoam has compressed. If it hasn’t, you can be reasonably sure that it hasn’t saved anyone’s life.“

It is doubtful whether soft-shell helmets provide a net safety benefit. From evidence provided in court:

“So in at least one case now, a High Court has decided that the balance of probability was, in the matter before the Court, that a cycle helmet would not have prevented the injuries sustained when the accident involved simply falling from a cycle onto a flat surface, with barely any forward momentum. …

the QC … repeatedly tried to persuade the neurosurgeons … to state that one must be more safe wearing a helmet than would be the case if one were not. All three refused to do so, claiming that they had seen severe brain damage and fatal injury both with and without cycle helmets”

Replacing safety for some with the illusion of safety

Before the helmet law, Australia’s bicycle helmet standard required hard shells. Government research warned of deficiencies in the standard, as helmets can increase brain injury.

The research recommended improvement to the standard. Instead, the government degraded Australia’s helmet standard to accommodate ”soft-shell helmets”. Soft-shell helmets are more comfortable and facilitate compulsory helmet wearing. However they provide little protection and can cause brain injury.

So what is the Australian standard for bicycle helmets? Strangely, it is not freely available to the public. In the parliament inquiry into Personal Choice, an Australian citizen managed to get a copy of it. He reports:

“the tests applied to the helmets in no way imitate the ways in which they would be required to be used on the roads. The fact that the helmets are dropped “without weight” onto a surface to determine their efficiency is a fraud! The testing of a helmet that doesn’t simulate a 70kg person falling at speed is providing people with a false sense of security that their helmet will protect them!”

The Australian standard is not designed to ensure protection. It seems like it is designed to provide a false sense of safety.

Although the standard was degraded, the Department of Transport misled its minister that it was being upgraded and would result in improved helmets.

Before the helmet law, about 30% of cyclists wore helmets like the one on the left. By degrading the helmet standard, the government legitimized a weaker helmet. Calling a polystyrene hat a “helmet” doesn’t give it protective abilities. Still, it can mislead people into believing that it provides more protection than it really does.

Bureaucrats have spent millions of taxpayers money on brainwashing propaganda such as “helmet save lives”, while hiding the fact that the Australian standard is not designed to provide meaningful protection. Whose interests are they serving?

Why isn’t the public warned about the risk of neck injury and severe brain injury from wearing a bicycle helmet? The warnings from the government own research agency (FORS) have not been communicated to the public.

After the helmet law, some claimed “success”, as the “helmet wearing rate” had increased. Yet useful helmets had been replaced with weaker ones providing minimal protection. The legislation had provided little more than the illusion of safety.

We have been sold a dud about bicycle safety. Wearing a helmet can make us feel safer. However feeling safe is different than being safe. The committee seemed unable to distinguish feeling safe from being safe. It lost focus on the initial goal to improve safety.

Victorian Government’s submission to the committee said:

“The incidence of bicycle helmet use has not yet reached a sufficiently high level anywhere in the world for a scientific examination of helmet effectiveness in injury reduction to be undertaken.”

Despite flimsy evidence of efficacy, the committee recommended compulsory helmet wearing.

blank

Setting the law

The RACS pressed the Victorian Government to make helmet wearing compulsory. The Victorian Parliament adopted a RACS recommendation for compulsory wearing, and legislation was announced. This increased pressure on the Federal Government to “do something”. The RACS was active in pressing the government. A former minister in the Hawke Government observed that after 1987:

“increasingly, the Government, and most importantly (Prime Minister) Hawke, became hostage to narrow and unrepresentative pressure groups.”

He also said the black spots program was not evaluated properly and was driven by opinion polls, a view supported by official documents. In 1988, the largest ever cycling casualty study was published. It involved more than eight million cases of injury and death to cyclists over 15 years. It concluded

“There is no evidence that hard shell helmets have reduced the head injury and fatality rates. The most surprising finding is that the bicycle-related fatality rate is positively and significantly correlated with increased helmet use.”

Rodgers, G.B., Reducing bicycle accidents: a reevaluation of the impacts of the CPSC bicycle standard and helmet use, Journal of Products Liability, 11, pp. 307-317, 1988.

This study focused on hard-shell helmets, that provide better protection than soft-shell helmets. The Federal Office of Road Safety (FORS) gave no warning about it to the ministers who decided on the compulsory helmet policy. The FORS did not act upon the 1985 committee’s recommendation that it should establish the costs and benefits of universal bicycle helmet usage. The FORS, the proper authority to advise government on the efficacy of helmet wearing, did no evaluation of it. The stated purpose of the compulsory helmet wearing was to reduce the cost of bicycling injuries. Yet the FORS did not seek advice from the National Health and Medical Research Council or other health authority. This was negligence.

The government ignored evidence showing that helmeted cyclists had a higher fatality rate

Just before the government decided to introduce compulsory bicycle helmets, an officially commissioned survey showed that public support for it was 92% for children and 83% for all riders. Politicians sometimes follow popular beliefs, regardless of their effectiveness:

“Modern politicians have become so adept at monitoring public opinion that they’ve developed a preference for wanting to be seen fixing problems rather than to actually fix them.”

In 1989, Prime Minister Hawke announced compulsory helmet wearing as Federal policy. This was a condition of providing funds to the states and territories for eliminating so-called “black spots” in roads.

Responses to enquiries in 1997 showed that no government in Australia, federal or state, made the necessary verification of the efficacy of helmets before imposing legislation. A study from Western Australia indicating that helmet wearers had more severe injuries appears to have been ignored.

The Prime Minister categorised compulsory wearing of bicycle helmets as a known and effective measure. This cannot be true as it had never been tried before. Government’s own research warned against increased brain injury from bicycle helmets. A trial for such experimental measure would have been appropriate. Instead, the government imposed across the nation an unproven policy without plans to assess its effectiveness.

blank

The consequences of negligence

The timing of the helmet law was odd as cycling safety was improving. Deaths of cyclists had been in long-term decline. Bicycle travel in Australia increasing by 10% a year from 1986 to 1989. Cycling is as safe as being a pedestrian. Why impose helmets only on cyclists? Why discriminate against a healthy and environmentally friendly mode of transport?

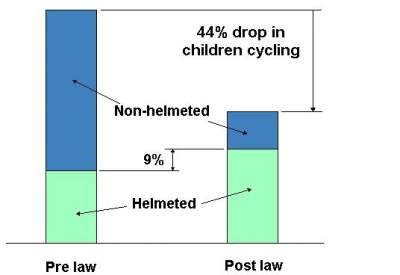

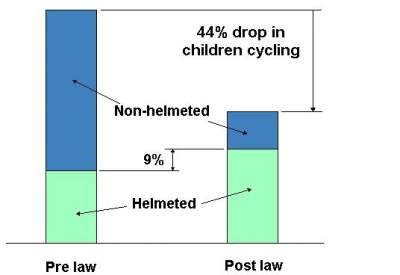

A side-effect of this policy has been to reduce cycling. This was predictable. In 1985, cycling had declined after some schools mandated helmets for students. It could have been measured consistently. Instead, cycling counts were mainly incidental to surveys of helmet wearing. These surveys revealed an immediate decline in cycling of about 30% for adults and 40% for children.

This reversed an uptrend growing at 10% a year. An independent assessment estimates that cycling was 50% below previous trend by 1996. Cycling as a transport declined the most, changing the image of cycling. Sport cycling rose in prominence, giving cycling an image as a dangerous sport. Australia now has the lowest female cycling participation in the world. Julian Ferguson, from the European Cyclists Federation, observed:

“Riding in New York or Australia is like running with the bulls — it’s all young males”

The main result of the helmet law has been to reduce cycling

The helmet law persuaded 569 child cyclists to wear a helmet, while 2,658 gave up cycling.

Surprisingly, the risk of death and serious injury increased by 50% for child cyclists after the law.

Dr Carwyn Hooper from St George’s University in London reports:

“Looking at evidence, it does not matter if people are wearing a helmet or not, any serious accident on a bike is likely to kill them,”

Before the law, cycling was increasing in popularity and becoming safer. After the law, cycling was falling and becoming more dangerous.

There is a well-known phenomenon called safety in numbers. Research published in the Injury Prevention journal concluded:

“the behavior of motorists controls the likelihood of collisions with people walking and bicycling. It appears that motorists adjust their behavior in the presence of people walking and bicycling … A motorist is less likely to collide with a person walking and bicycling if more people walk or bicycle. Policies that increase the numbers of people walking and bicycling appear to be an effective route to improving the safety of people walking and bicycling.”

A key factor for cycling safety is the number of cyclists. This is called “safety in numbers”.

The fewer cyclists, the more dangerous cycling becomes.

blank

According to “safety in numbers”, a 44% decline in cycling increases the risk of accidents by 41%. A 9% increase in helmet wearing cannot compensate for a 41% increase in accidents. The helmet law has increased the risk of injury by increasing the risk of accident.

blank

Denying the failure

In the mid 1990s, evidence emerged that the helmet law had failed to improve safety. A bicycle activist who supported compulsory helmet wearing looked at the data and concluded:

“It is fair to say that, so far, there is no convincing evidence that Australian helmet legislation has reduced the risk of head injury in bicycle crashes.”

Several researchers reported this, but state governments ignored the warnings. Once people have invested time and effort in something, they are reluctant to admit they have made a mistake. Bureaucrats became entrenched in their position. As noted by University of Armidale researcher Dr Dorothy Robinson:

“mandatory bicycle helmet laws increase rather than decrease the likelihood of injuries to cyclists …

Having more cyclists on the road is far more important than having a helmet law, for many reasons …

[the] governments [which introduced the helmet laws] do not like to admit they’ve made mistakes“.

The Australian government attitude towards its bicycle helmet law matches its national emblem

Bureaucrats started funding policy-driven studies defending its helmet law. Such “studies” use biased statistics, resulting in misleading claims.

The helmet law was introduced as a part of a package of road safety measures including a crackdown on speeding and drink driving. The number of cyclists dropped significantly. Any assessment of the helmet law must take into account these confounding factors. Yet many government-funded “studies” like this one did NOT adjust for this. Such negligence is difficult to comprehend. It is odd that these mistakes favor the legislation while the government funds the “research”.

Bill Curnow, a scientist from the CSIRO, wrote as a conclusion in a scientific article:

“Compulsion to wear a bicycle helmet is detrimental to public health in Australia but, to maintain the status quo, authorities have obfuscated evidence that shows this.”

One of the “studies” done by an Australian federal government agency in 2000 claimed to provide

“overwhelming evidence in support of helmets for preventing head injury and fatal injury”.

This claim was rebutted in 2003:

“the meta-analysis … takes no account of scientific knowledge of [brain injury] mechanisms”

The government agency did not reply to the rebuttal, giving up on its claim. Despite being discredited, this analysis is still used by bureaucrats to defend the official policy.

This study was re-assessed in 2011 by an independent researcher who concluded:

“This paper … was influenced by publication bias and time-trend bias that was not controlled for. As a result, the analysis reported inflated estimates of the effects of bicycle helmets …

According to the new studies, no overall effect of bicycle helmets could be found when injuries to head, face or neck are considered as a whole”

Following CRAG submission to the Prime Minister in 2009, the federal government has abandoned its compulsory helmets policy.

Despite the repeated empty claims from politicians that

“helmets save lives and lower the severity of injuries”,

independent researchers are not fooled:

“If helmet laws were effective, we should have seen a reduction in head injuries,” she said. But instead, we saw a reduction in cycling, which leads to increased sedentary lifestyle diseases – obesity, strokes, heart disease. By discouraging cycling, helmet laws actually increase health costs.”

Even helmet salespeople do make such claims. After being asked

“Can your helmet save your life?”,

a helmet salesperson shrugged and laughed uncomfortably, before responding

“Can it?” “Well, not save your life, no.”

What is it that politicians know that helmet salespeople don’t?

In 2011, the Queensland Government commissioned a “study” to defend its policy. Only 13 days were given to produced this study. The study was then significantly edited several times (to favor the legislation) by the Department of Transport and Main Roads. The government then used this fake “study” to dismiss calls to review the helmet law.

In 2011, the New South Wales government funded a study trying to deny that helmets can aggravate brain injury. This risk has been reported at high speeds. The “study” set up unrealistic conditions at low speed, then magically generalized the results. This is deceitful as these unrealistic conditions are not representative of real life accidents.

There is a stark contrast between the claims from policy-driven “studies” and independent researchers. In the view of independent researchers from Norway:

“no studies have found good evidence of an injury reducing effect”.

While British doctors say:

“[A helmet law] gives out the message that cycling is dangerous, which it is not. The evidence that cycling helmets work to reduce injury is not conclusive. What has, however, been shown is that laws that make wearing helmets compulsory decrease cycling activity. Cycling is a healthy activity and cyclists live longer on average than non-cyclists. …

Since nowhere with a helmet law can show any reduction in risk to cyclists, only a reduction in cyclists, why would any country want to bring in a law for something which is clearly not effective at reducing the risk to cyclists?”

In the view of an Australian surgeon who operates on cyclists:

“The best evidence is that [a helmet] doesn’t make any difference to serious head injury when riding a bicycle …

initial research used to back the mandatory laws was “deeply flawed and criticised”. Some newer findings, he said, showed that these laws could increase the chance of serious injury. “On a society-wide basis, it seems as though the compulsory wearing of helmets is diminishing the number of people riding bicycles” he said. “The number one health concern is heart attacks and obesity. “Anything that can be done to decrease that would be a good thing.” “

The policy-driven studies have not fooled the rest of the world, who chose to shun this policy.

blank

Adding scaremongering tactics

In the 1990s, compliance surveys revealed that about 30% of cyclists still ignored the law. In response, transport authorities staged an extensive media campaign. Authority figures appeared on television asserting that people NEED to wear a helmet because cycling is dangerous. Loaded slogans like “Where’s your helmet?” were used relentlessly.

In advertising, you don’t need proof. Advertising associates a strong positive emotion with a message. For example associating a feeling of safety with a helmet. It doesn’t have to be true.

Transport authorities still fund misleading campaigns like this 2011 radio ad that claims:

“Don’t think that little ride to the shops warrants wearing [a helmet]? Well I’ve got news for you. Even on a short ride you can have a big fall and you can suffer a MAJOR brain injury”

Is scaring people away from cycling an appropriate use of taxpayer’s money?

A bicycle activist created an amusing parody of this deceptive message.

This scaremongering is not true. Cycling is not particularly dangerous, no more than being a pedestrian:

“risk assessment reveals that cycling is not a more risky activity than the other modes of transport. …On the other hand, risk assessment does provide evidence of the much greater vulnerability of pedestrians.”

Helmet ads often use scaremongering tactics. As a result, many people become scared of cycling.

Helmet ads often use scaremongering tactics. As a result, many people become scared of cycling.

Powerful emotional testimonies claiming “my helmet saved my life” were prominently broadcast. Deceitful techniques suggested that cyclists would suffer brain injury unless they wore a helmet.

This is deceitful as soft-shell helmets are known to increase the risk of brain injury. Scientific research reveals:

“Protecting the brain from injury that results in death or chronic disablement provides the main motivation for wearing helmets. Their design has been driven by the development of synthetic polystyrene foams which can reduce the linear acceleration resulting from direct impact to the head, but scientific research shows that angular acceleration from oblique impulse is a more important cause of brain injury. Helmets are not tested for capacity to reduce it and, as Australian research first showed, they may increase it.”

Helmets do not provide a solution to severe brain injury. Yet scare tactics exploiting fear of chronic disability have been used to promote them. This leads to an exaggerated opinion of the protection provided by helmets.

When we keep hearing the same statement again and again, we end up believing it. This is a well-known manipulation technique, mentioned by Daniel Kanheman in his acclaimed book “Thinking fast and slow“:

“A reliable way to make people believe in falsehoods is frequent repetition, because familiarity is not easily distinguished from truth. Authoritarian institutions and marketers have always known this fact.”

The deceitful advertising campaign was effective. Most Australians now believe that cycling is dangerous. Such propaganda has created a culture of fear. Cycling kept declining further. By 1996, cycling in Sydney had declined by 48%. People overestimate the protection provided by a polystyrene “helmet”. A UK cyclist survey following helmet promotion campaigns reports:

“the majority of the people surveyed do have an exaggerated opinion of the effectiveness of cycle helmets, and an exaggerated opinion of the risks of cycling, and that the two are associated …

the exaggerations in the promotional material are likely to both prevent some people from cycling because of the fear of the risk, and to induce risk compensatory behaviour in those who chose to cycle and wear a helmet”

blank

A surprising increase in accidents and injuries

Cycling injuries increased following the helmet law:

Hospital admission data: Number and percentage of cyclists admitted, Western Australia.

Despite 37% fewer cyclists, cycling injuries kept rising after the helmet law.

After the helmet law was enforced in July 1992, the number of cyclists dropped by 37%. In 1993, cycling hospitalisations were slightly below 1991, despite 37% fewer cyclists. The risk of injury per cyclist increased. Cycling injuries kept rising. In 2000, the risk of injury was twice what it was before the helmet law.

This is similar to what was observed in New South Wales (NSW), where the risk of injury more than tripled.

For child cyclists in NSW, the risk of death and serious injury increased by more than 50%.

What’s going on?

How can accidents and injuries keep rising after an increase in helmet wearing?

Perhaps it has something to do with the false sense of safety fostered by deceitful helmet promotion campaigns. A false sense of safety can induce people to take more risks, leading to more accidents and more injuries. This is risk compensation, a well-known safety factor:

“the law of unintended consequences is extraordinarily applicable when talking about safety innovations. Sometimes things intended to make us safer may not make any improvement at all to our overall safety”

Risk compensation is the tendency to take more risks when wearing safety equipment.

Lured by a false sense of safety, helmeted cyclists have more accidents.

blank

“the rate of head injuries per active cyclist has increased 51 percent just as bicycle helmets have become widespread. …

the increased use of bike helmets may have had an unintended consequence: riders may feel an inflated sense of security and take more risks. …

The helmet he was wearing did not protect his neck; he was paralyzed from the neck down. …

”It didn’t cross my mind that this could happen,” said Philip, now 17. …

”I definitely felt safe. I wouldn’t do something like that without a helmet.” ”

Safety experts recognise the role of risk compensation. From the New York Times article:

”People tend to engage in risky behavior when they are protected,” he said. ”It’s a ubiquitous human trait.”

Even cyclists who discount the daredevil effect admit that they may ride faster on more dangerous streets when they are wearing their helmets.

Risk compensation also affect motorists who tend to be less careful around helmeted cyclists. As reported in a study published by the University of Bath in the UK:

“Bicyclists who wear protective helmets are more likely to be struck by passing vehicles”

Both the behaviour of helmeted cyclists and surrounding motorists increases the risk of accidents.

blank

The neglected human factor

Why these surprising results? A key neglected factor is the impact that wearing a helmet has on cyclists behaviour. For some people, it means no more cycling. For others it means taking more risks. Neither reaction improves cycling safety or public health. Helmets affect risk taking, as reported by the Institute of Transport Economics in Norway:

“There is evidence of increased accident risk per cycling kilometre for cyclists wearing a helmet”

Helmets encourage people to ride faster, as reported by the Risk Analysis international journal:

“those who use helmets routinely perceive reduced risk when wearing a helmet, and compensate by cycling faster”

Increased speed significantly the severity of injuries in case of an accident, as reported in 2012 by the Monash University Accident Research Centre:

“Chances of a head injury increased threefold at speeds above 20km/h and fivefold at speeds above 30km/h”

What is the point wearing a helmet if it induces people to ride faster? At best, a helmet can only reduce a 50 km/h impact to the equivalent of a 45 km/h impact.

A slow and cautious rider without a helmet is less at risk than an overconfident helmeted rider taking risks at higher speeds. With a helmet law, the safer type of cycling is illegal while the more dangerous behavior is vindicated. This is the irony of a counterproductive policy. A 2012 study published by the Institute of Transport Economics in Norway concludes:

“at least part of the reason why helmet laws do not appear to be beneficial is that they disproportionately discourage the safest cyclists.”

In Australia, the cyclist fatality rate is five times greater than in the Netherlands. The serious injury rate is 22 TIMES greater. The fatality rate per commuter cyclist is 27 times higher in Sydney, Australia than in Copenhagen, Denmark.

John Pucher, a US professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey, has researched how several countries have made cycling safe. Infrastructure, legislation to protect cyclists, training and measures to discourage car use are key. Helmets played no part in making cycling safer. John Pucher said:

“Compulsory wearing of helmets was “a Band-Aid strategy” adopted by governments shying away from more difficult initiatives of building separated cycle ways, calming neighbourhoods and educating drivers and riders.”

An obsession with helmets can result in neglecting more effective safety measures. This might explain why Australia’s serious injury rate is 22 TIMES greater than in the Netherlands

Australian road safety “experts” have ignored the link between helmets and risk-taking. They have difficulty admitting the helmet law has failed. They seem unable to distinguish between the intention to improve safety and the naive way it is attempted. They have ignored the increase in injuries following the helmet law. This is irrational and harmful.

“One of the great mistakes is to judge policies and programs by their intentions rather than their results.”

Milton Friedman, Nobel price economist

Health on the Move 2, a report from an independent British society of public health and transport practitioners and researchers, reports:

“The failure of mass helmet use to affect serious head injuries, be it in falls or collisions, has been ignored by the medical world, by civil servants, by the media, and by cyclists themselves. A collective willingness to believe appears to explain why the population-level studies are so little appreciated. ….

The disconnect between received wisdom and the facts is stark.”

blank

Start of renewal

The four rooms of change.

Before renewal, people usually go through denial, then confusion.

blank

In 1994, the Northern Territory of Australia relaxed its helmet law and reduced its enforcement. The helmet wearing rate is the lowest in Australia. Cyclist hospitalisations per capita are the lowest and cycling to work is three times the national average.

Bike share schemes have been successful all over the world. Even in cities without a history of cycling, the benefits can be significant. For example, in Seville, Spain:

“Traffic congestion and pollution are declining for the first time in 30 years. Businesses are thriving along bike routes and around the newly improved public spaces that are breathing fresh life into the central city. The number of car trips into the historic city center has plummeted from 25,000 a day to 10,000”

Bike share schemes have been successful all over the world, except in Melbourne and Brisbane.

In 2010, Melbourne introduced a bike share scheme. Usage is 20 TIMES lower than in Dublin, a city of comparable size. Danish urban planner Mikael Colville-Andersen, who specialises in cycling, noted:

“Good ideas tend to travel and this idea, that you simply must wear a helmet when you cycle, has not. What does that tell you? You are the fattest country in the world, you should be encouraging cycling, not convincing people it’s dangerous.”

With its low speed and upright position, bike share is safe. In London, after 7 million trips, there were no fatalities and only 9 injuries requiring hospitalisation. The serious injury rate is 3 times lower than for all cyclists.

Bike share schemes in Mexico City and Tel Aviv have boomed since the Mexican and Israeli Government repealed their mandatory helmet laws. The Australian cities of Sydney, Perth, Fremantle and Adelaide have declared their support for helmet law reform.

Even in the US, where the belief in helmets is strong, people are questioning the suitablility of helmets for bike share:

“Pushing helmets really kills cycling and bike-sharing in particular because it promotes a sense of danger that just isn’t justified — in fact, cycling has many health benefits …

Statistically, if we wear helmets for cycling, maybe we should wear helmets when we climb ladders or get into a bath, because there are lots more injuries during those activities.”

blank

Summary

Bicycle helmets tend to

- induce a false sense of safety that increases the risk of accidents

- encourage cyclists to go faster, increasing the severity of injuries

- increase the risk of neck injury and brain injury

It is easy to take for granted the protection provided by helmets. Evidence indicates that the protection is minor, while helmets increase the risk of accidents.

Are extra accidents worth the “protection”?

After reviewing evidence in a court of law, NSW District Court Judge Roy Ellis concluded:

“Having read all the material, … I frankly don’t think there is anything advantageous and there may well be a disadvantage in situations to have a helmet and it seems to me that it’s one of those areas where it ought to be a matter of choice.”

The process to introduce the helmet law was complacent:

- The government did not verify the efficacy of helmets.

- The government failed to warn the public that helmets can increase brain injury.

- Government research recommended to strengthen Australia’s helmet standard. Instead, it was degraded to accommodate soft-shell helmets.

- The legislation discriminates against cycling, a safe, healthy, and environmentally friendly mode of transport. The consequences on cycling participation were given little consideration.

- The government imposed an experimental helmet law nationwide, with neither a trial period nor plans to assess its effectiveness.

Such negligence has contributed to the increase in cycling injuries following the helmet law.

The government has attempted to obfuscate its policy failure by commissioning misleading “studies”.

An obsession with helmets can result in neglecting more effective safety measures. This might explain why Australia’s serious injury rate is now 22 TIMES greater than in the Netherlands

This policy has failed to achieve its stated goal of reducing the cost of cycling injuries. It has reduced cycling. This results in a loss of health benefits, incurring public health costs.

Good intentions.

Bad results.

blank

Acknowledgement: Most historical information comes from this article, and from CRAG submission to the Prime Minister in 2009.

Following CRAG’s submission, the federal has government abandoned its compulsory helmets policy.